At the 2023 Summit for a New Global Financing Pact in Paris, French President Emmanuel Macron declare yourself that “policy makers and countries should never have to choose between reducing poverty and protecting the planet”. That may be true, but if European politicians want to make significant progress in climate finance flows to Africa, they need to make some tough choices about where to direct their resources.

2024 is a decisive year for climate finance: the next United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in November will focus on climate finance, while the World Bank’s concessional lending arm, the International Development Association, will begin to replenish its funds as part of the next fundraising round. However, current policy proposals do not adequately recognize the hard resources and political limits that constrain any increases in climate finance. Discussions at summits and high-level forums have often adopted a mindset of abundance, rather than scarcity, generating a surprising number of different policy proposals for climate finance. This resulted in a lack of focus. With COP29 only a few months away, it is unclear what the main policy objective is for Europe.

Europeans are interested in pushing for more climate finance in Africa. The lack of affordable finance for climate projects in Africa is a key obstacle for the continent to achieve its adaptation and mitigation goals. African countries have too is expressed significant dissatisfaction with the global financial system, which hindered the Europe-Africa relationship. Now, with his downfall Chinese investment in Africa, there is an opportunity for Europe to strengthen its role as Africa’s partner of choice.

But European politicians must deal with an inconvenient truth: political and financial capital is limited, and they must prioritize where resources should flow. The technically, politically and legally complex nature of many policies in climate finance means that implementing any of the proposed solutions is a difficult task. Europeans have so far spread these resources too thinly across a range of policy proposals and therefore struggle to innovate in different areas. Fixing the funding gap will require greater focus.

Limited capital and ambiguity

African countries will require one estimated at $2.5 trillion external financing between 2020 and 2030 to implement their Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. Current flows fall far short, with available funding amounting to just 12 percent of that target.

This is because all potential finance providers in African countries either have limited funds or cannot transfer them. The most obvious financiers of climate finance on the continent – African countries themselves – lack access to affordable finance. This is largely the result of the “highest for a long time” international borrowing rates, which many African countries have priced out. These high interest rates also limited the flow of resources from developed countries or from multilateral development banks (MDBs). Meanwhile, reduced fiscal space and swipe right in many European countries it caused total overseas development assistance from traditional donors to least developed countries fall in 2023. And while ambitionThe revision of the MDBs is laudable, they are not realistic in the short to medium term, with geopolitical competition between China and the United States limiting any major capital increases or shareholder changes at the World Bank and IMF.

There is also limited political capital to build enough momentum to make progress on a range of climate policies. Major climate finance proposals such as the redistribution of special drawing rights (SDRs) – a type of reserve currency issued by the IMF – are often seen by developed countries as low priority and high difficulty. Low priority because heightened geopolitical tensions mean European countries are more concerned with security and domestic issues than development, and high difficulty because of the technical and complex nature of climate finance. Indeed, whether a climate finance policy is successful or not depends on a series of complex legal, economic and political considerations. European policy makers should focus significant political capital to achieve policy innovations in this area.

The abundance mindset

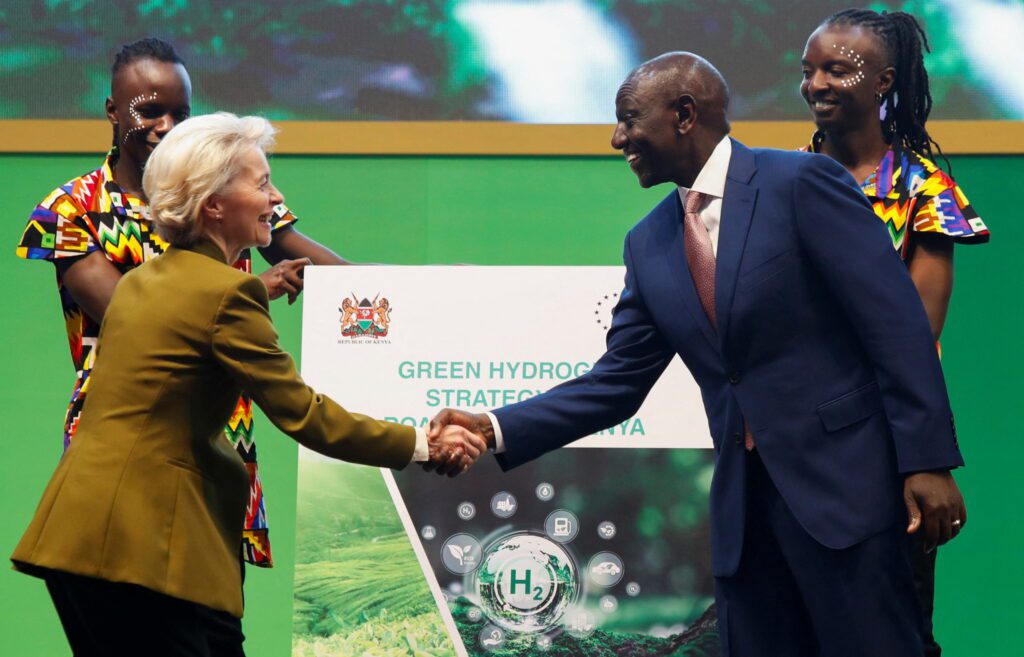

Despite this strongly negative international economic outlook, major climate finance statements and events have not framed their proposals with this limitation in mind. The Bridgetown Initiative, for example, led by the prime minister of Barbados, Mia Motley, called for $1 trillion in additional multilateral lending (on top of the current about $700 billion), numerous debt relief mechanisms, a new $500 billion SDG issue, and “reconstruction grants for any country just at risk of a climate disaster.” In the meantime, the summary of funding for the Paris summit proposed 11 different action points and the Nairobi Declaration that emerged from the Africa Climate Summit in Kenya in September called for about 54 different policies to address climate issues in Africa.

The reason for this is obvious: these summits and initiatives are political events for European countries to show their commitment to increasing funding and for African and developing countries to ask for more. And their multilateral form makes it difficult to distill the views of everyone at the table into a few clear points. But Africa’s climate finance needs are too urgent to continue living in this abundance mentality.

Africa’s climate finance needs are too urgent to continue living in this abundance mentality

In the spotlight

If European politicians can agree on where to focus their efforts, they can advance reforms within the World Bank and the IMF and increase climate finance in Africa despite the constrained international financial environment.

A key example of the importance of focus is the long and protracted redistribution process of SDRs. The reserve currency initially seemed a promising policy option to increase climate finance in African countries. After the economic shock of covid-19, the IMF made SDRs available on a dramatic scale, issuing $650 billion in SDRs. But, as they are distributed according to the respective shares of IMF member states, this allocation left many high-income countries with significant amounts of SDRs that they did not need. As a result, the G20 committed in 2021 to transfer $100 billion from their SDRs to developing countries.

In response, and as a result of increased financial and policy focus at the time, the IMF established the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST), to support the pre-existing Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT). The IMF and the G20 intended that the two trusts could use SDRs from high-income countries to lend on soft terms to low-income countries.

However, since then, the loss of political momentum along with many legal challenges have hindered SDR redistribution. Both the PRGT and the RST have hit capacity, partly due to a lack of subsidies and staff at the IMF, and therefore cannot take on more SDRs. That’s gone $47.5 billion of SDR value without a redistribution mechanism. In addition, both bodies have fight to disburse funds to low-income countries due to IMF regulations on which countries can receive RST financing. Other solutions have also proven difficult. Some central bank chiefs, such as European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde, have blocked efforts to redistribute SDRs through other MDBs, such as the African Development Bank. Nearly three years after pledging $100 billion, less than 1 billion dollars have been disbursed to developing countries.

Some proposals, such as that of the African Development Bank, are critical hybrid capital proposalas well as the concept of SDR-linked bonds proposed by Brad Setcher, Steven Pantuanoand Theo Maret, show viable, alternative pathways for SDR redistribution. By focusing policy resources aimed at adapting and clarifying eurozone regulations and making greater allocation of subsidy resources, the IMF could successfully use SDRs for climate finance.

In the run-up to COP29, and with limited financial and political capital, European and African politicians have to make some hard choices and bet on specific policies. They need to choose where to focus their attention and resources to make meaningful changes and accept that not all climate finance proposals can be winners. The Bridgetown Initiative yet recognized this need, noting its aim “to support progress … through greater understanding, focus, prioritization, coordination and unity of effort”. If European policymakers do not agree on a focus, both they and their African counterparts could walk away from COP29 with nothing to show for all their efforts.

The European Council on External Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications represent only the views of their individual authors.